Happy new year, and happy new post! Last time we dipped our toes in how to interact with Gemini APIs from Python and built a chat bot. This time, let’s take that a bit further and come up with a way for a user to describe a picture and have Vertex AI create one that fits that description. And this time we’ll see how to deploy it to the web so other people can use it.

This post tries to be accessible to beginners but still useful to experienced developers. If you are already comfortable with writing Flask web apps, you can go ahead and skip ahead to the Generating an image section and work forward from there.

Set up

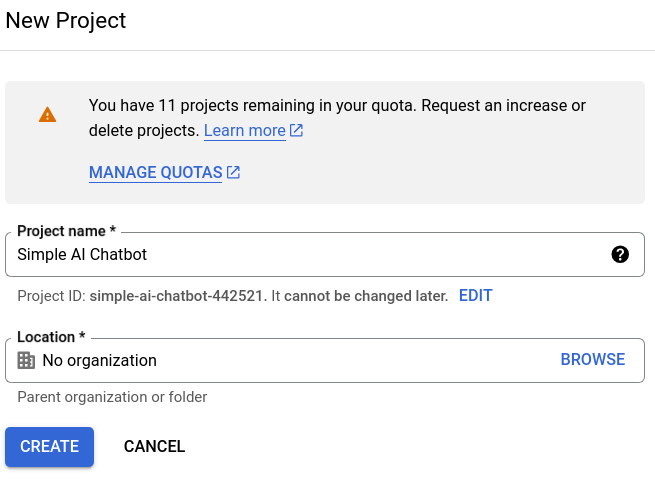

If you followed the previous post and built the chatbot yourself you’ve already created the necessary environment for this example. You need a Google Cloud account and a cloud project to work in. You’ll work in a “local” Python environment with the necessary tools installed. That means a new folder and a new virtual Python environment. (Why is “local” in quotation marks? Because I am including using Cloud Shell as “local”, since it behaves almost exactly like a shell on your own machine but with most of the prerequisites already in place.)

Create and change to a new new working folder, set the project using gcloud config, and create empty files to work in: main.py for the Python code and requirements.txt for the packages it will need:

mkdir demo-image-generation

cd demo-image-generation

gcloud config set project silver-origin-447121-e9

touch main.py

touch requirements.txtThe project ID shown above is a random one generated by Google Cloud because the name I chose, demo-image-generation, was already in use.

The application skeleton

You’re going to create a Python web application using Flask for this. It just needs to be one page: an editable input box for entering the description (called the prompt in AI) and the image generated. When the user submits the form on that page your application will read the prompt, call the necessary API, and then return a new page that includes the new image. The user can then refine the prompt and submit the refined one for another image.

It should look more or less like this:

The prompt of “a cute puppy” should be whatever the user entered, and the gray block should be the actual generated image. A basic web page to show this is:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head><title>Demo Image Generation</title></head>

<body>

<h1>Demo Image Generation</h1>

<form action="/" method="post">

<input type="text" name="prompt" id="prompt" value="{{prompt}}">

<input type="submit" value="Generate Image">

</form>

<br><img src="{{image_url}}">

</body>

</html>Your program will have to insert the correct values for the {{prompt}} the user entered and {{image_url}} we generated, so we will treat this HTML as a template for the returned page. Create a folder called templates and save the above code in it as index.html.

That’s the web page code; let’s take a look at the Python program. You are going to use the Flask framework, which is both powerful and simple, a combination I really appreciate. A basic Flask program looks like this:

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

# Request handlers go here

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True, host='0.0.0.0', port=8080)The first two lines import the Flask library and create a Flask object in the global variable app. That is followed by request handlers that describe how to handle requests for different paths, such as the home page – we’ll look at those in a minute. And the last section says that if this code is run directly, rather than imported by another program, start the Flask app object running in debug mode.

This code can run standalone or imported into another web server that’s more scalable and performant. In that case the other web server will call on this module’s app variable to handle requests for it. That happens in Cloud Run, which we will be using to deploy this to the web later on in this post.

Go ahead put the code above into your main.py file, and add the line below to requirements.txt:

flaskThen install the modules there and run the program:

pip install -r requirements.txt

python main.pyWhen you open a page from this server you will get a 404 Not Found response. That’s because the program does not yet specify how to handle requests for any page. Let’s add that to the skeleton before we go on to work on real functionality. When the home page is requested, the program should return the index.html file we showed above.

You’ll declare the request handler with Flask’s app.route decorator. That decorator makes whatever function declared immediately after it run whenever the specified path is requested. Here’s the code:

@app.route("/"):

def home():

return render_template("index.html")This declares that requests to / (the home page) will run the home function and return its output to the browser. In this case, that output will be the contents of templates/index.html. Add this function to your main.py program, and change the initial import statement to:

from flask import Flask, render_templateThen try running it again. You should see a page similar to the mock-up shown earlier. There will be no prompt filled in nor image displayed because the render_template function will replace those with empty values since we didn’t provide any values to it. You’ll fix that in the next section.

Home page handler

When the home page is called with a POST request indicating a form was submitted, the handler should get the prompt from the form, generate an image for it, and return the index.html page with that prompt and a URL for that image filled in.

The program can get the submitted prompt from the form with the Flask request object. You’ll need to change the first line to also import that:

from flask import Flask, render_template, requestThe function can fill in the placeholders in the index.html file by providing the correct values as parameters to render_template. So your code will be:

@app.route("/", methods=["GET", "POST"])

def home():

if request.method == "GET": # No form submitted

return render_template("index.html")

# POST with a form submitted

prompt = request.form["prompt"]

image_data = generate_image(prompt)

image_url = get_url(image_data)

return render_template("index.html", prompt=prompt, image_url=image_url)There are several new things in the code above. First, this handler now receives both HTTP GET (fetch a page) and POST (submit a form) requests. Without the methods property on the @app.route decorator, Flask would only send GET requests to it; POST requests would get a 405 Method Not Allowed response.

Second, the handler checks whether this is a GET request or not. For a GET request it just returns the empty template, just as before. But for a POST request it use the Flask request object to get the value of the submitted prompt in the form. And then it generates the image and returns the page with the prompt and image URL inserted. Here’s the response to the prompt “a cute happy black and white shih tzu puppy” with the completed program (from the next section):

Next is the real work in generating an image. But in the spirit of taking small steps, let’s just create placeholders for the hard work of generating an image and creating a URL for it:

def generate_image(prompt):

return b"" # Empty byte string

def get_url(image_data):

return ""Since generate_image is supposed to return binary data, the placeholder returns a byte string instead of a normal string.

Update the main.py file to have the code above and try running it again. The first home page request should return an empty form, and submitting it should return a page with prompt filled it. It also returns an image URL, but since that’s blank there’s nothing displayed.

Generating the image

Ready for the real point of this post, generating an image from a prompt? Well, here it finally is!

The function will use Google Cloud’s Vertex AI library to generate the image, so an import statement needs to be added near the top of the program. It also uses the Python tempfile standard library:

from vertexai.preview.vision_models import ImageGenerationModel

import tempfileSince this is not a standard library it will also need to be installed, so add this line to requirements.txt:

vertexaiAnd now, the code to create the image:

def generate_image(prompt):

model = ImageGenerationModel.from_pretrained("imagegeneration@006")

response = model.generate_images(prompt=prompt)[0]

with tempfile.NamedTemporaryFile("wb") as f:

filename = f.name

response.save(filename, include_generation_parameters=False)

with open(filename, "rb") as image_file:

binary_image = image_file.read()

return binary_imageThe actual AI image generation is done in the first two lines. ImageGenerationModel.from_pretrained creates a model object from a saved, pretrained one. That returned model has a method called generate_images that will use the model to create images based on the prompt. That method returns an iterable list of as many images as requested, defaulting to one image. So element 0 of this list is an object representing the generated image.

This immediately raises the question, where do you get pretrained models? It looks like imagegeneration@006 is one, but where did that magic name come from? It’s in Google’s Vertex AI image generation documentation, though it takes a bit of digging to find it. AI documentation is incredibly broad and deep, so this direct pointer may be one of the most valuable things in this blog post for you!

Once the function has this image object it needs to get the binary contents of it to return it to the function’s caller. The documentation for the object shows only way to get the contents of it: saving it to a file. I was surprised there was no more direct way to do this, but maybe a future library update will have it. In any case, saving it to a file is the only way for now, which is what the rest of the function does by writing it to a temporary file and then reading the file in binary mode.

Creating the URL

The code needs to create a URL pointing to the image. That’s going to be a little tricky; the image is in memory only, and there’s no web server configured to return it now. And the web page is normally going to fetch the image with a separate request and the local variable data containing the image won’t exist in that context. It might not even exist anywhere by then since we hope to deploy this to Cloud Run, a serverless platform. It’s possible that each separate web request could be handled by a separate server, so even if the image data is saved in a file the file might not be on the machine receiving the URL.

The program can’t keep the image data in memory nor in the filesystem of its server. Though keeping it in the filesystem would almost always work in the real world, which is worse in a way than never working. It would lead to an expectation that would fail just when it was most important.

So how do you get the image to the web browser? The program could save the image data outside of the web server, such as in Google Cloud storage. But you would have to arrange for it to be cleaned up eventually and make sure each image has a unique name so browsers didn’t end up with other pages’ images. Or, it could stuff the entire image into the URL put in the web page itself!

Data URLs aren’t widely known, but they are a great tool for serverless applications that create an return images. When the web server receives a request to create an image it can create a URL containing the image and return it as part of the web page. Then there’s only one HTTP request, the one submitting the form asking for an image. When the browser needs to display the image the data is right there inside the page.

The format of a data URL is the keyword data followed by a colon, then the content type, a semicolon, the keyword base64, a comma, and then the base64 encoded data, such as:

data:image/png;base64,YWJjZGVmOf course a real data URL for an image file will be much larger. That’s okay; Python, web servers, and web browsers will all be fine with it.

Here’s the code to generate a data URL for the binary image data it is sent:

def get_url(image_data):

base64_image = base64.b64encode(image_data).decode("utf-8")

content_type = "image/png"

image_uri = f"data:{content_type};base64,{base64_image}"

return image_uriThe code uses the standard base64 Python library, so add an import line at the top of the file:

import base64The completed program

That’s all the pieces. Put them together and you have a program to generate images based on descriptions you enter. The combined code is also available in this GitHub repository.

Want to let a friend use the program? They’d have to get their own Google Cloud accounts, or maybe visit and use your logged in laptop. That’s less than ideal. The final step today is going to be deploying this program to the web so you can share it. There are plenty of ways to do this, but this uses Cloud Run.

Deploy to Cloud Run

After all the lead up to this point this step is likely to be disappointingly simple. Run this command in your shell:

gcloud run deployAnswer all the questions. The defaults are usually fine, except near the end, when you’ll be asked whether to allow unauthenticated invocations. Answer Y instead of the default N for this.

Wait a minute – do you really want to allow just anybody to use your program? Remember, you’ll be paying for it. Surely you want to restrict this to people you select?

You probably do, but Cloud Run’s authenticated invocation restriction can’t do that for. If you don’t allow unauthenticated invocations no web browser can ever access it. That’s because Cloud Run’s authentication mechanism is intended for use by other programs connecting to your Cloud Run service as an API, not for users running web browsers.

You can protect your service with a login screen, but it’s a much bigger deal than you might think. Maybe I’ll write a post on how to do that soon. The concepts, but not how to put them all together in front of your service, are described in this blog post of mine, however.

To get back to the point of this post, once you have deployed this program to Cloud Run you will have a web address that anyone can use to generate images with your program. At your expense. Which brings us to the concluding section of this post.

Cleaning things up

Your program will incur some cost every time somebody uses it. If that doesn’t appeal to you, you should either use the cloud console to delete the service you created, or go to the dashboard and shut down the entire project you created for this. Shutting down a project is the surest way to make sure there won’t be any more charges from it.

I hope you found this very detailed post useful. Most of the time I won’t include every tiny step as I did here, but the first time I encountered this AI stuff some apparently straightforward steps were pretty confusing to me. I’ve tried to clear all that up here.